Recent trends after five decades of official bilingualism

Start of text box 1

Highlights

-

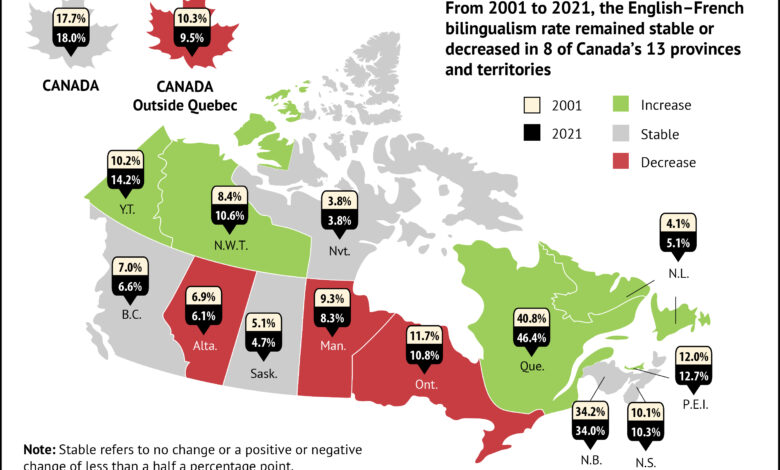

In 2021, nearly one in five people (18.0%) in

Canada could have a conversation in English and French, representing close to 6.6 million

people. While this proportion has never been this high in a census, it has

remained stable compared with 2001 (17.7%). -

In Quebec, the rate of English–French

bilingualism rose from 40.8% in 2001 to 46.4% in 2021, while over the same

period, it fell from 10.3% to 9.5% in Canada outside Quebec overall. However, the

rate of bilingualism in both official languages was increasing in Newfoundland

and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Yukon and the Northwest Territories. -

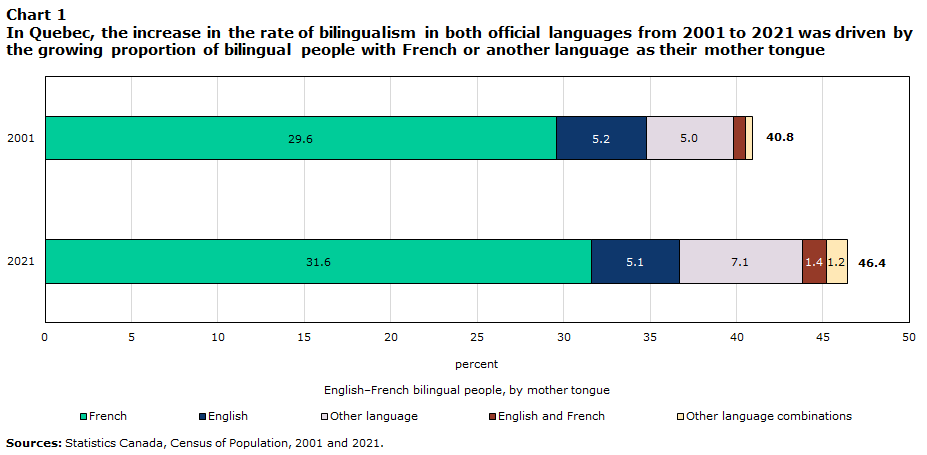

The increase in the rate of bilingualism in both

official languages in Quebec was driven by two key factors. One factor is the

rise in the English–French bilingualism rate of the population with a French

mother tongue from 36.6% in 2001 to 42.2% in 2021. The other factor is an

increase in the demographic weight of the population with another mother

tongue, i.e., a language other than English or French, with just over half of

this population (50.8% in 2021) being able to have a conversation in Canada’s

two official languages. -

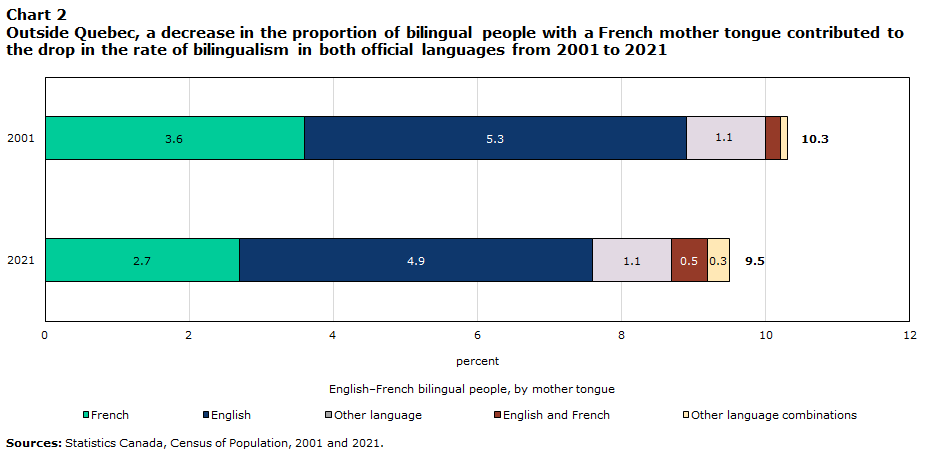

Two key drivers are also behind the decrease in

the rate of English–French bilingualism observed since 2001 in Canada outside Quebec. The first is the

decline in the demographic weight of the French-mother-tongue population, of

which a high proportion is proficient enough in both official languages to

conduct a conversation (85.3% in 2021). The second is the decline in the English–French

bilingualism rate of the population with another mother tongue, which fell from

5.7% in 2001 to 4.7% in 2021. -

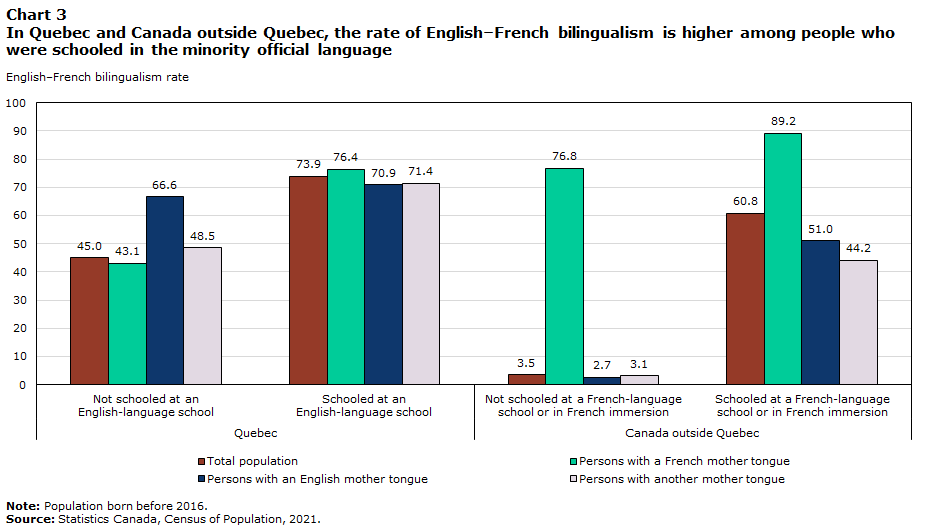

In Canada outside Quebec, approximately three in

five people (60.8%) who attended a French-language school or a French immersion

program could have a conversation in both official languages, compared with 3.5%

of those who did not attend these schools or immersion programs.

End of text box 1

Introduction

The Official Languages Act was adopted

in 1969, making English and French Canada’s official languages. Official bilingualism

is both symbolic and tangible. On one hand, it reflects the importance of

English and French in Canada’s history and identity, and in the everyday life

of communities across the country. On the other, having an officially bilingual

federal government is a guarantee to those living in Canada that the government

will provide its services in English and in French, where demand warrants. This

is why greater English–French bilingualism is of particular interest in Canada:

it fosters mutual understanding and communication between English- and

French-speaking communities and it ensures that the right of people living in

Canada to receive federal services in either official language is respected.

With each census, the number of people who are

able to have a conversation in English and French has continued to grow in

Canada, totalling almost 6.6 million people in 2021. From the early 1960s to

the turn of the century, the rate of English–French bilingualism in Canada rose

sharply from 12.2% in 1961 to 17.7% in 2001. Since then, the proportion of the

Canadian population who is bilingual in English and French has been relatively

stable, with the bilingualism rate reaching 18.0% in 2021. Nonetheless, this is

the highest proportion ever observed in a census.

The stability in the bilingualism rate

observed recently is the result of two diverging trends: the increase in the

rate of English–French bilingualism in Quebec, which offset the decrease

observed outside the province.

Today, Statistics Canada is publishing an

analysis of the evolution of English–French bilingualism in Canada, which also

examines how changes in the demographic weight and bilingualism rate of

populations with an English, French or other mother tongue have contributed to

this evolution. Lastly, this report provides a glimpse into the link between

schooling in the minority official language and English–French bilingualism.

Start of text box 1

Parlez-vous français? Do you speak English?

English–French bilingualism, or bilingualism in both official languages, refers to the ability to have a conversation in English and French, Canada’s two official languages. In the census question on knowledge of official languages, people report their ability to have a conversation in English, French, English and French, or neither.

The very first questions on the ability to speak English and French appeared in the 1901 Census of Population. At the time, 14.7% of Canada’s population knew English and French.

End of text box 1

The rate of English–French bilingualism increases in Quebec and falls in Canada outside Quebec

In Canada and in each province and

territory, except Alberta and Nunavut, there were a record number of bilingual

English–French people in 2021.

However, since the 2001 Census, the growth

of the population who speaks English and French well enough to conduct a

conversation has been lower or similar to the growth of the rest of the population

in many provinces and territories, resulting in a declining or stable English–French

bilingualism rate in these provinces and territories. For example, in New Brunswick,

Canada’s only officially bilingual province, the English–French bilingualism rate

has been stable,Note 1

standing at 34.2% in 2001 and 34.0% in 2021. In contrast, the bilingualism rate

was higher in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Yukon,

and the Northwest Territories in 2021 than 20 years earlier.

In Canada outside Quebec as a whole, the

rate of English–French bilingualism was on an upward trend from 1961 (6.9%) to

the turn of the century (10.3% in 2001). Since then, with the exception of a

slight rebound between 2011 and 2016, this rate fell from one cycle to the

next, totalling 9.5% in 2021.

In Quebec, aside from a small decline from 2001

to 2006, the English–French bilingualism rate has been rising with each census

since the early 1960s, increasing from 25.5% in 1961 to 40.8% in 2001, then

reaching 46.4% in 2021. In other words, almost one in two people in Quebec could

have a conversation in Canada’s two official languages in 2021.

Data table for map 1

| Rate of bilingualism in both official languages | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2021 | Change from 2001 to 2021 | |

| Canada | 17.7 | 18.0 | Stable |

| Canada outside Quebec | 10.3 | 9.5 | Decrease |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4.1 | 5.1 | Increase |

| Prince Edward Island | 12.0 | 12.7 | Increase |

| Nova Scotia | 10.1 | 10.3 | Stable |

| New Brunswick | 34.2 | 34.0 | Stable |

| Quebec | 40.8 | 46.4 | Increase |

| Ontario | 11.7 | 10.8 | Decrease |

| Manitoba | 9.3 | 8.3 | Decrease |

| Saskatchewan | 5.1 | 4.7 | Stable |

| Alberta | 6.9 | 6.1 | Decrease |

| British Columbia | 7.0 | 6.6 | Stable |

| Yukon | 10.2 | 14.2 | Increase |

| Northwest Territories | 8.4 | 10.6 | Increase |

| Nunavut | 3.8 | 3.8 | Stable |

The increase in English–French

bilingualism in Quebec and the decrease observed in Canada outside Quebec since

the turn of the century can be observed in the geographic distribution of

Canadians who can have a conversation in both official languages. In Canada,

the proportion of English–French bilingual people living in Quebec increased

from 55.6% in 2001 to 59.2% in 2021, bringing it closer to the level observed

in 1961 (60.0%).

Moreover, the rate of bilingualism in both

official languages was higher in regions where English- and French-language

communities are in close contact, either in the same territory or in adjacent

territories. These regions are, in fact, among those with the highest rates of English–French

bilingualism in the country. For example, in 2021, Canada’s census metropolitan

areas (CMA) with the highest bilingualism rates were GatineauNote 2 (64.6%), Montréal (56.4%),

Sherbrooke (46.0%) and Moncton (45.9%).

| Census metropolitan area (CMA) | English–French bilingualism rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2021 | Variation from 2001 to 2021 | |

| percent | percentage points | ||

| Quebec (province) | 40.8 | 46.4 | 5.6 |

| Gatineau | 64.0 | 64.6 | 0.6 |

| Montréal | 52.4 | 56.4 | 4.0 |

| Sherbrooke | 41.1 | 46.0 | 4.9 |

| Québec (CMA) | 32.6 | 41.5 | 8.9 |

| Trois-Rivières | 26.0 | 32.4 | 6.4 |

| Drummondville | 23.7 | 30.0 | 6.3 |

| Saguenay | 18.4 | 23.7 | 5.3 |

| Non-CMAs | 24.6 | 30.4 | 5.8 |

| Canada outside Quebec | 10.3 | 9.5 | -0.8 |

| Moncton | 47.0 | 45.9 | -1.1 |

| Greater Sudbury | 40.4 | 36.7 | -3.7 |

| Ottawa | 36.2 | 36.4 | 0.2 |

| Fredericton | 20.6 | 22.5 | 1.9 |

| Other CMAs | 8.1 | 7.3 | -0.8 |

| Non-CMAs | 10.4 | 9.5 | -0.9 |

From 2001 to 2021, the English–French

bilingualism rate increased in all large urban centres in Quebec. This rate

rose 5.6 percentage points in the province during this period, but the

increase was even larger in the CMAs of Québec (+8.9 percentage points), Trois-Rivières

(+6.4 percentage points) and Drummondville (+6.3 percentage points), and

in regions outside CMAs (+5.8 percentage points). In contrast, the growth

of the bilingualism rate was smaller in the CMAs of Gatineau (+0.6 percentage

points) and Montréal (+4.0 percentage points)—two CMAs that, in 2001, already

had the highest bilingualism rates in the country.

The rate of English–French bilingualism declined

0.8 percentage points from 2001 to 2021 in Canada outside Quebec, as well

as in Greater Sudbury (-3.7 percentage points) and Moncton (-1.1 percentage

points), but remained stable (+0.2 percentage points) in Ottawa.Note 3 In contrast, the

bilingualism rate increased in Fredericton (+1.9 percentage points), New

Brunswick’s capital, during the same period.

Lastly, the English–French bilingualism rate

was even higher in certain municipalitiesNote 4

in regions with large proportions of people in a minority language situation. For

example, in 2021, more than four in five people were English–French bilingual

in Fort-Coulonge (82.0%) in Quebec’s Outaouais region, and in Bouctouche (81.2%)

in southeastern New Brunswick.

In Quebec, French speakers learning

English and immigration drive the English–French bilingualism

rate upward

Across Canada, the prevalence of English–French

bilingualism varies according to the first language learned in childhood, i.e.,

mother tongue.Note 5

In Quebec, the rate of English–French

bilingualism was 46.4% in 2021. For many decades, the bilingualism rate of

Quebeckers with an English mother tongue has been higher than the rate for the provincial

population, totalling 67.1% in 2021. Because this English-speaking population

is a minority in the province, it is more likely to come into contact with the

other official language community and learn its language.

Similarly, the English–French bilingualism rate

was higher than the average among Quebeckers with another mother tongue, with

just over half being able to have a conversation in Canada’s two official

languages in 2021 (50.8%). Among people with another mother tongue—more than

three-quarters (76.4%) of whom are immigrants or non-permanent residents—English

and French are at least the second or third languages they learned.

Lastly, the rate of bilingualism in both

official languages of Quebeckers with a French mother tongue was lower than the

average provincial rate in 2021. However, the bilingualism rate of this group grew

the most from 2001 to 2021, increasing 5.6 percentage points from 36.6% to

42.2%. Growth in the bilingualism rate was slower in the populations with an

English mother tongue (+1.0 percentage point) or another mother tongue (+0.4 percentage

points).

From 2001 to 2021, the English–French bilingualism

rate of the French-mother-tongue population in Quebec rose among both younger

people and core-aged adults in the labour market. Over this period, this rate increased

more than 12 percentage points for each five-year age group from 10 to 44 years.

In addition, the bilingualism rate of the population with a French mother

tongue rose in all the province’s regionsNote 6

and large urban centres.

The demographic weight of Quebec’s

French-mother-tongue population decreased from 80.9% in 2001 to 74.8% in 2021. By

comparison, the demographic weight of the population with an English mother

tongue was more stable, edging down from 7.8% to 7.6%, while the weight of the population

with another mother tongue advanced from 10.0% to 14.0%, driven by immigration.

The combined effect of the changes in the demographic weights and the

prevalence of bilingualism based on mother tongue accounts for the increase in

the English–French bilingualism rate in Quebec from 2001 to 2021.

Data table for chart 1

| English–French bilingual people, by mother tongue | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2021 | |

| percent | ||

| French | 29.6 | 31.6 |

| English | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| Other language | 5.0 | 7.1 |

| English and French | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Other language combinations | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| Total | 40.8 | 46.4 |

The proportion of Quebeckers who could

conduct a conversation in Canada’s two official languages increased 5.6 percentage

points from 2001 to 2021. A large share of this gain is attributable to the growth

in the proportion of the population who is bilingual in English and French and

has a French mother tongue (+2.0 percentage points) or another mother

tongue (+2.1 percentage points). On one hand, the increase in the bilingualism

rate of the French-mother-tongue population more than offset the decrease in

its demographic weight. On the other, the bilingualism rate of the population

with another mother tongue was stable from 2001 to 2021, but its demographic

weight increased thanks to immigration.

The increase in the English–French

bilingualism rate in Quebec from 2001 to 2021 was also driven by the growth of

the bilingual population with more than one mother tongue, i.e., individuals

who learned English and French (+0.7 percentage points) or another

language combination (+0.8 percentage points) at the same time in

childhood. For more information on individuals with more than one mother tongue,

see the box entitled “Bilingual from childhood.”

Fewer French speakers and more Asian-born

speakers of another language contribute to the decline in the rate of

bilingualism in both official languages in Canada outside Quebec

Like in Quebec, a large proportion of the population

in Canada outside Quebec whose first language is the minority official

language—French, in this case—could carry on a conversation in both official

languages in 2021 (85.3%). By comparison, the English–French bilingualism rates

of individuals with an English or another mother tongue were lower; around 1 in

14 English speakers (7.1%) and fewer than 1 in 20 speakers of another language

(4.7%) were proficient enough in both official languages to conduct a conversation.

In Canada outside Quebec, the English–French

bilingualism rate of the population with another mother tongue fell 1

percentage point from 5.7% in 2001 to 4.7% in 2021. In comparison, this rate

was more stable among French speakers (+0.2 percentage points) and English

speakers (no change).

The English–French bilingualism rate of the

population with an English mother tongue remained stable over this period due

to diverging trends between certain age groups. One of these trends is the

rising bilingualism rate of young English speakers aged 5 to 14, which increased

from 8.8% in 2001 to 11.2% in 2021. One factor that drove this rate upward was

the growing number of young people in French immersion programs. In contrast, the

bilingualism rate of English speakers aged 20 to 29 decreased from 12.0% in 2001

to 9.0% in 2021.

The 1 percentage-point decrease in the

bilingualism rate of the other-mother-tongue population is due in part to a

change in the composition of this population by place of birth. From 2001 to

2021, the proportion of people with another mother tongue who were born in an

Asian country rose sharply on account of immigration (from 35.6% to 55.2%), while

the proportion of this population born in Europe dropped from 27.9% to 15.8%. In

2021, the English–French bilingualism rate was lower among individuals with

another mother tongue born in Asia (2.0%) than among their counterparts born in

Europe (6.0%), in the Americas (excluding Canada) (8.1%) or in Africa (13.8%). The

growing proportion of Asian-born non-official language speakers and the decline

in the proportion of non-official language speakers born in Europe therefore

contributed to the drop in the bilingualism rate of non-official language

speakers in Canada outside Quebec.

Start of text box 1

Multilingual despite a lower rate of bilingualism in both official languages

In Canada outside Quebec in 2021, more than one in eight people were Asian-born and had another mother tongue. Of these people, 2.0% could have a conversation in English and French. Although their rate of bilingualism in both official languages is lower, these individuals were multilingual. In fact, one-quarter (25.0%) could have a conversation in at least three languages, be it an official or another language. Most often, these individuals knew English and at least two other non-official languages. The ability to have a conversation in French was rarer.

In addition, of Asian-born individuals with another mother tongue who were living in Canada outside Quebec in 2021, the English–French bilingualism rate was higher among those who had immigrated during their childhood (5.2%), since they were able to start or continue their schooling in Canada. The bilingualism rate was also higher among people born in certain Asian countries, such as Lebanon (23.6%) and Iran (4.7%), while it was lower among people born in the Philippines (0.6%) and India (0.9%).

End of text box 1

From 2001 to 2021, the demographic weight

of the population with a French mother tongue in Canada outside Quebec decreased

(from 4.2% to 3.2%), as did the weight of the English-mother-tongue population

(from 74.6% to 69.0%). In contrast, the demographic weight of individuals with

another mother tongue rose from 20.0% to 24.0%. The combined effect of the

change in the demographic weights of these populations and their knowledge of

official languages accounts for the decrease in the English–French bilingualism

rate in Canada outside Quebec over this period.

Data table for chart 2

| English–French bilingual people, by mother tongue | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2021 | |

| percent | ||

| French | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| English | 5.3 | 4.9 |

| Other language | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| English and French | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Other language combinations | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Total | 10.3 | 9.5 |

In both 2001 and 2021, English was the

mother tongue of more than half of bilingual English–French people in Canada outside

Quebec.

In 2021, 9.5% of people in Canada outside

Quebec could have a conversation in English

and French, a decrease of 0.8 percentage points from 2001. Much of this decrease

stems from the decline in the proportion of the bilingual population whose mother

tongue is French (-0.9 percentage points). The proportion of bilingual people with

an English mother tongue also fell during this period (-0.4 percentage

points). However, this downturn was offset by the growth of the bilingual population

whose first languages learned in childhood were English and French (+0.3

percentage points) and of the bilingual population with another combination of

mother tongues (+0.2 percentage points).

Lastly, although people whose mother tongue

is a non-official language make up a growing proportion of the Canadian population

outside Quebec, the decline in their rate of bilingualism in both official

languages held the proportion of bilingual people with another mother tongue in

Canada outside Quebec stable at 1.1% in 2001 and 2021.

Start of text box 1

Bilingual from childhood

Since the turn of the century, a growing proportion of Canadians have

reported having learned two or more languages at the same time in childhood, be

it a combination of English, French or another language. In 2001, this

proportion was 1.3% and rose to 3.8%Note 7 in 2021. More in-depth analysis is required to better understand this

increase. Among the many factors that may have contributed to this gain is

the increasing number of children who grow up in families where more than one

language is spoken at home, such as in exogamousNote 8 or immigrant families.

The English–French bilingualism rate of people with more than one

mother tongue attests to the fact that they first learned more than one

language in childhood. For example, in Quebec in 2021, the bilingualism rate of

those with English and French as their mother tongues was 93.3%, while the

rate for those with another mother tongue combination stood at 58.6%. The

corresponding proportions in Canada outside Quebec were 83.3% and 9.3%, respectively.

However, not everyone whose mother tongues are English and French

were able to have a conversation in both official languages at the time of

the census. Sometimes, people who do not fluently speak one of the first

languages they learned feel they can no longer have a conversation in that

language, even though they can still understand it. This is especially true

as people get older. For example, in Quebec, the rate of bilingualism in both

official languages of people with English and French as their mother tongues

was 96.7% among speakers aged 10 to 29, compared with 82.1% among those aged 75 and

older.

End of text box 1

The English–French bilingualism rate

peaks among individuals who attended primary or secondary school in the

minority official language

The ability to have a conversation in a

second language varies by a person’s age and educational pathway.Note 9 For example, in 2021, the

English–French bilingualism rate was higher among Quebec residents who attended

an English school and residents of Canada outside Quebec who attended a French

school or a French immersion program for all or part of their primary or

secondary education than among individuals who did not attend these schools or

programs.

In Quebec, close to

three-quarters of people who attended an English-language schoolNote 10 (73.9%) reported being

able to have a conversation in Canada’s two official languages in 2021, compared

with 45.0% of people who did not attend an English-language school, a gap of 28.9 percentage

points. The difference in the bilingualism rate of people schooled in English

and those who were not was greater among individuals with a French mother

tongue (33.3 percentage points) or another mother tongue (22.9 percentage points), and smaller

among people with an English mother tongue (4.3 percentage points).

Data table for chart 3

| Total population | Persons with a French mother tongue | Persons with an English mother tongue | Persons with another mother tongue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English–French bilingualism rate | ||||

| Quebec | ||||

| Not schooled at an

English-language school | 45.0 | 43.1 | 66.6 | 48.5 |

| Schooled at an

English-language school | 73.9 | 76.4 | 70.9 | 71.4 |

| Canada outside Quebec | ||||

| Not schooled at a French-language school or in French immersion | 3.5 | 76.8 | 2.7 | 3.1 |

| Schooled at a

French-language school or in French immersion | 60.8 | 89.2 | 51.0 | 44.2 |

Similarly, in Canada outside Quebec, the English–French

bilingualism rate in 2021 was higher among individuals schooled in FrenchNote 11 (60.8%) than

among those who were not (3.5%). The difference was especially large among

those with an English mother tongue (48.3 percentage points) or another

mother tongue (41.1 percentage points), while it was smaller among those

with a French mother tongue (12.4 percentage points).

Lastly, there are a number of reasons why a

person schooled in the minority official language may report not being able to

conduct a conversation in both official languages. For example, some people may

have only done part of their schooling (e.g., one year) in the minority

official language. Or it may have been years since they finished primary or

secondary school, and during those years, they have not spoken the minority

official language enough to continue being able to have a conversation. Likewise,

some people may, over time, report no longer being able to have a conversation

in the first language they learned. Further studies are needed to get a better

understanding of the different life pathways associated with the loss or

maintenance over time of the ability to have a conversation in a language.

Looking ahead

This article gives an overview of recent

trends associated with the evolution of the English–French bilingualism rate in

Quebec, in Canada outside Quebec and in Canada. The results of the 2021 Census

and previous censuses provide insight into how the change in the demographic

weight of groups of speakers as well as their bilingualism rate led to a record

proportion of Canadians who were able to have a conversation in both official

languages in 2021.

For the first time, the 2021 Census results

shed light on the importance of the language of schooling at the primary and

secondary levels to learn the official languages. Future studies on topics such

as participation in French immersion programs in Canada outside Quebec will give

a clearer picture of this situation.

Additional information

The key 2021 Census results on knowledge of English and French in Canada were published on August 17, 2022, in the Daily article “While English and French are still the main languages spoken in Canada, the country’s linguistic diversity continues to grow” and in the infographic “More than one language in the bag: The rate of English–French bilingualism is increasing in Quebec and decreasing outside Quebec.”

Additional information on knowledge of official languages can be found in data tables and the Census Profile.

Reference products are designed to help users make the most of 2021 Census data. These include the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021, the Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021 and the 2021 Census of Population questionnaires. The Languages Reference Guide is also available.

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Étienne Lemyre of Statistics Canada’s Centre for Demography, with the assistance of other staff members of this Centre and the collaboration of staff from the Census Subject Matter Secretariat, the Census Operations Division, the Communications Branch, and the Data Access and Dissemination Branch.

Source link